Cervical Screening Wales, along with Public Health Wales, have made the decision to extend the time between cervical screenings for women aged 25 to 49. If human papillomavirus (HPV) is not detected in the smear test, women will now wait five years rather than three until their next cervical screening.

Professor Allison Fiander, Chair of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Cardiff University says that “the screening test is now so sensitive that it is a very safe intervention, and a very safe change to the cervical screening programme”.

Previously, cytology was the main method for testing abnormal cells. Cervical screening samples were examined under a microscope to determine if any cells could possibly develop into cancer.

Over the past four years a new testing process has been developed and rolled out across the UK following a successful pilot programme by the National Screening Committee, which will test screening samples for HPV before cytology, rather than after.

The new methods of testing allow for cases of cervical cancer to be treated earlier making it a more accurate way of screening women for dangerous cells.

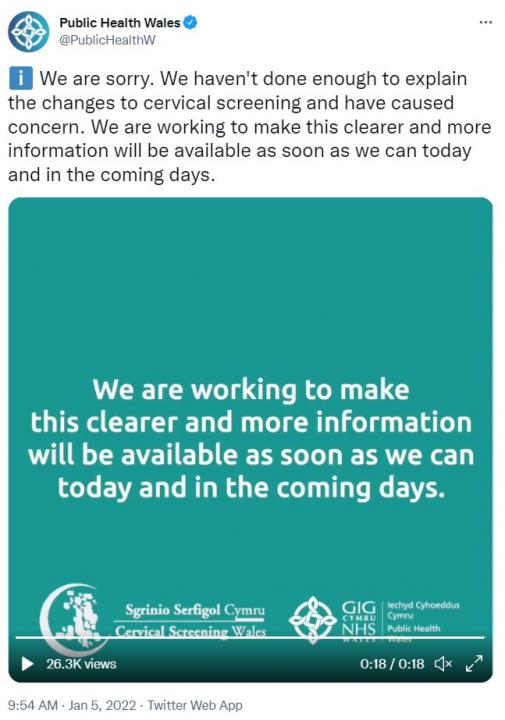

A petition to reverse the decision made by Public Health Wales received over 1.2 million signatures by concerned members of the public and directed a huge backlash onto PHW for a lack of evidence on why the decision was made.

Professor Fiander said: “What we didn't explain clearly enough is that if you had an abnormal smear, and HPV is detected, then things wouldn't change for you. You would still be followed up closely. So, it was just that explanation that was lacking that made women so worried.

“I think it was a missed opportunity to say this is actually good news, because the fact is we've improved cervical screening, so we're going to reduce the number of women that go on to develop cancer”.

In April 2019, the Department of Health rolled out the HPV vaccine to boys aged 12 to 13 as well as girls. Prof Fiander added: “The HPV vaccine has dramatically decreased the rates of infection by high-risk HPV. It's a virus that most of us will come into contact at some point in our lives - 90% of women will come into contact with HPV at some point in their lives. It's a very common virus, it's like getting a cold; nearly everybody has had a cold and it is the same for HPV.

“If we really fulfil the potential of vaccination and cervical screening that's based on HPV testing, we could virtually eliminate or eradicate cervical cancer in the UK”.

In 2003, the age for beginning cervical screenings was lowered to 25 years old for anyone with a cervix. In a UK Health Security Agency blog, the question ‘why is the age that women are first invited for screening not lower?’ is answered by explaining that investigating a woman’s cervix at a young age can do more harm than good.

Alison Fiander added that: “HPV infection is so common in young people when they start to become sexually active. If you screen below the age of 25, nearly everybody would have HPV. By the time you get to 25, if you've come into contact with HPV, you should have cleared it by yourself. And the ones that have got HPV at 25 are the ones that we need to look at more closely to make sure that they don't go on to develop cell changes”.

Professor Fiander is confident that the change to screening intervals “won’t make any difference to how carefully the smears are looked at because a lot of it is automated, especially for HPV testing. The samples are prepared, and then the machine does the HPV test.

“However, it does mean that perhaps resources could be saved and used for other parts of the screening programme, such as focusing on reaching the women who currently aren’t coming forward for cervical screenings.”

Prior to the change in the screening intervals, 28% of women aged 25 to 64 were not having a cervical screening within the timeframe advised for their age, with one in three women saying they were too embarrassed about their body, according to a study by Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust.

“The women that are worried that they're not going to have their screening tests so often are not the ones at risk. It's the ones that don't go for cervical screening that are at a greater risk”, says Prof Alison Fiander.

“It is an intimate examination. It doesn't take very long. It is a little bit uncomfortable. It is not painful or anything, but it is embarrassing for women. Regardless of how nice the clinic surroundings are, how nice your nurses or doctors are, it is a little bit embarrassing. People don't like the screening test, so the fact that you can have it less often is actually good news.

“It might be that eventually we can self-test where a swab is inserted into the vagina and then that swab can be tested for HPV. There is currently research going around for that, which would hopefully make cervical screenings more acceptable to the women that are just too embarrassed to come to the doctors”.

Home testing kits have already undergone initial trials, with 600 women taking part. Once the kits have been trailed on a wider scale, the tests are set to become available to order online to encourage more women to come forward.