Research from the University of Nottingham has shown how the NHS can better use its resources and reduce unnecessary blood tests.

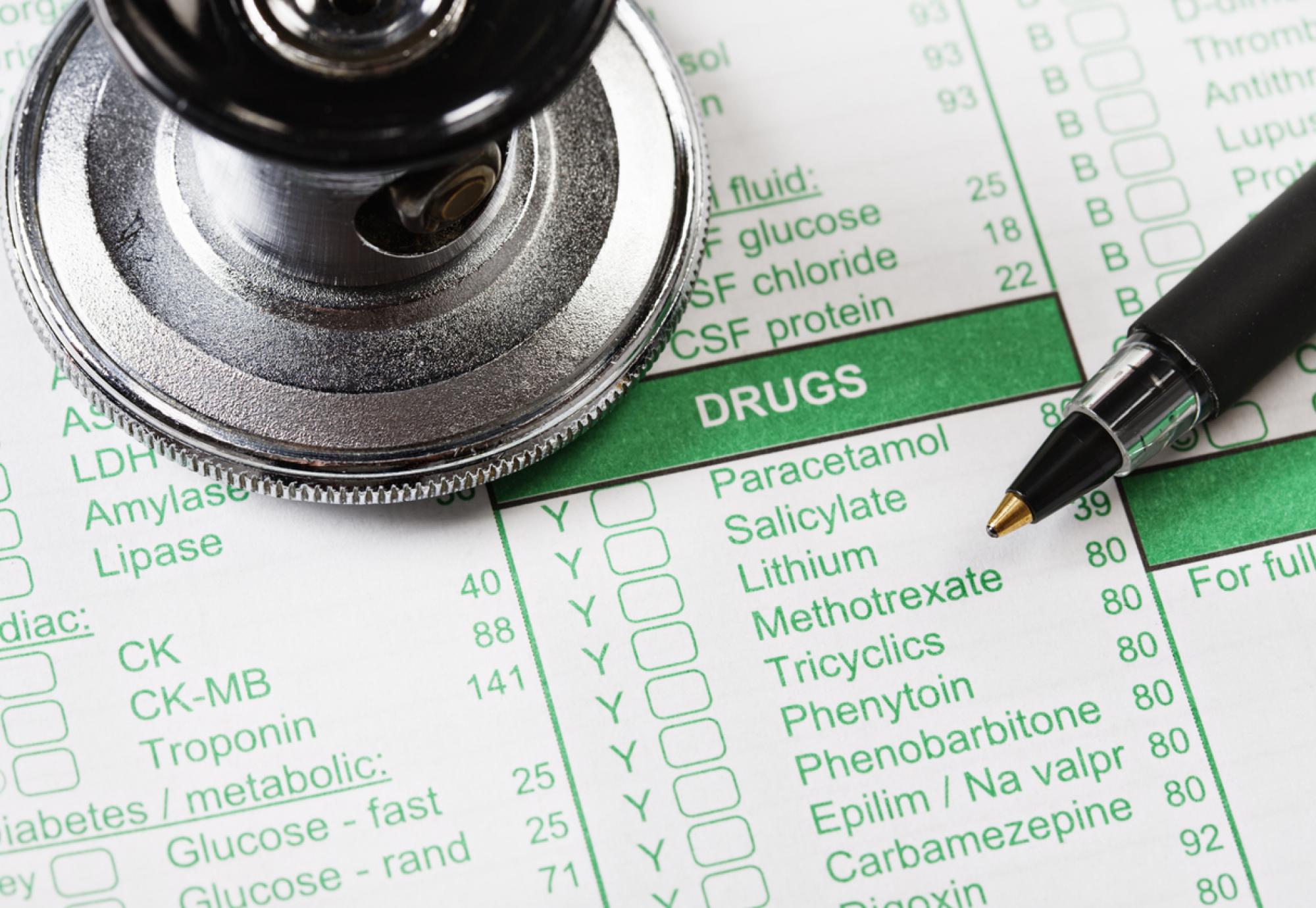

The revelations come after researchers devised a method of predicting the risk of side effects in those taking the immune suppressing medicine known as methotrexate.

More than a million people take methotrexate to treat things like rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis in the UK. While it has established itself as an effective form of therapy for a variety of illnesses, it can lead to side effects like liver complications, kidney problems and low blood count.

These issues typically present themselves during the first couple of months of the treatment, meaning patients are often given blood tests every two-to-four weeks along with three monthly tests for everyone taking methotrexate.

But in a study funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), researchers have found a way of using data from electronic health records and consultations to give people a bespoke risk assessment.

The researchers believe the method of predicting when abnormal blood test results may occur could be deployed by GPs and specialists, enabling more flexibility when deciding how often a patient requires blood tests.

Professor of Rheumatology at the University of Nottingham, Abhishek Abhishek, led the study.

“Many patients with inflammatory conditions take methotrexate for several years – often for more than 10 years – and the results of this study will be useful in reducing unnecessary monitoring blood-tests for them over a long-period of time,” said Prof Abhishek.

“Implementing these results could vastly improve the utilisation of NHS resources, save patients time and also protect the planet by reducing the carbon footprint of monitoring tests.”

Experts from Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the Universities of Birmingham, Sheffield and Keele also worked on the project.

The director of NIHR’s Health Technology Assessment Programme, Professor Andrew Farmer, added: “This could improve people’s lives and ease pressures on the NHS by freeing up resources for other patients who may need them more."

The full study results were published in the British Medical Journal.